It all started with Delvin McMillian but(t) didn’t end with Ashley Crandall. Ashley had ridden with Ride 2 Recovery on an upright bike and wanted to continue, but was suffering from a wrist condition that would not allow her to effectively squeeze the brake handles on her bike. She turned to Ride 2 Recovery for a solution. Acknowledged as a leader in building and donating adaptive bikes, Project Hero began innovating designs that allow injured cyclists to ride in 2009.

It all started with Delvin McMillian but(t) didn’t end with Ashley Crandall. Ashley had ridden with Ride 2 Recovery on an upright bike and wanted to continue, but was suffering from a wrist condition that would not allow her to effectively squeeze the brake handles on her bike. She turned to Ride 2 Recovery for a solution. Acknowledged as a leader in building and donating adaptive bikes, Project Hero began innovating designs that allow injured cyclists to ride in 2009.

“Ashley Crandall wanted to continue riding but her condition made that really difficult. It motivated us to create something that allows her to continue to ride and brake despite her physical challenges,” said John Wordin, president and founder of Project Hero. “So we built on an existing design we had seen, put a few pieces together as a test, worked out the bugs and created the “butt brake,” which we could use for Project Hero Riders.

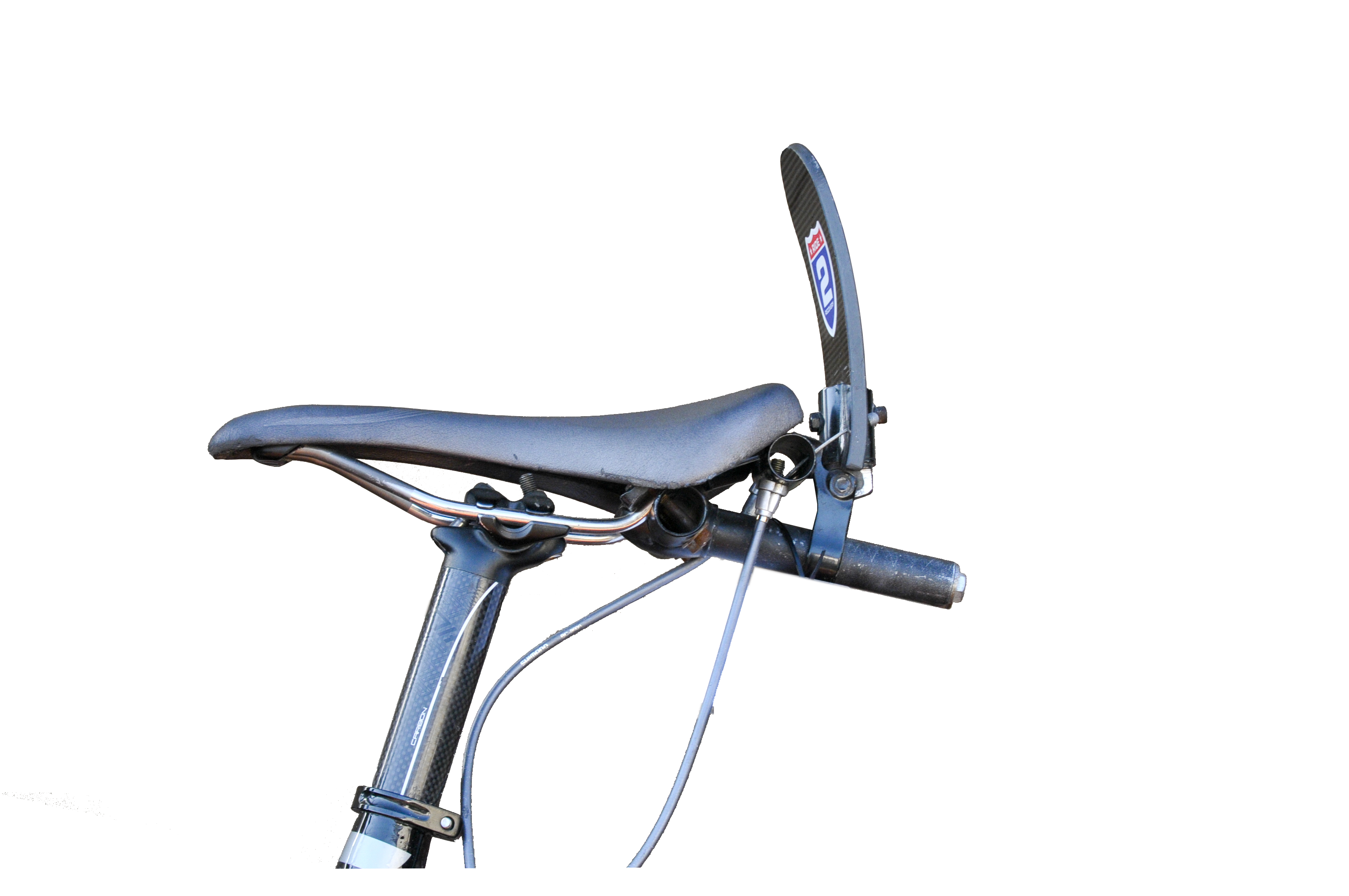

The Butt Brake allows the rider to brake by pressing their lower back against a vertical paddle mounted at the rear of the saddle. When pushed, the paddle operates the brake cables, giving the rider the ability to stop the bike hands-free.

After she was medevac’d from her 3rd deployment in 2009, Ashley began to experience reoccurring pain in her wrists that she believed was from working years as a helicopter mechanic. But the pain turned into shock waves, numbness, and eventually loss of function in her hands. She was seen by Occupational Therapy and, after a year of braces and exercises, ended up having surgery on her left wrist to address the cause of the nerve damage. Doctors told her they could only stop the progression and couldn’t fix the damage already there which would significantly affect her time in the saddle.

“It started off as a simple adjustment. Scotty Moro would lessen the pull resistance on my bike brakes a little at a time. Once he couldn’t play with it anymore, he moved my shifters to the right side (my “good” side) and ran a cable splitter to allow me to activate both brakes from the same lever.”

That solution worked for a couple of years but on one Challenge, only a few miles away from the end of the ride, Ashley’s entire right arm went numb and limp. True to Ride 2 Recovery style, she didn’t want to quit so close to the finish line, so former professional rider and Ride 2 Recovery stalwart Wayne Stetina held onto the back of her jersey for the remaining 10 miles, manually slowing her down when needed.

“That was the first time I realized that my inability to brake was becoming a hazard to other riders and that I might have to quit riding. I was devastated!” she said. “Riding had become so integral to my therapy that my doctors had actually written it into my treatment plan. My chain of command often bent leave rules for me because they witnessed how transformed I was every time I came back from a Challenge.”

Riding had become as important to her “as breathing, and I had no idea what I’d do without it.” She had heard about the existence of a no-hands braking system that had been created for mountain bikes and asked Ride 2 Recovery if they could create something similar for her road bike. “Of course Scott was up for it, and there was no way I was going to pull out of that ride!” she said. Although she wasn’t able to try out the new adaptation until the first day of the 2013 California Challenge, it didn’t take her long to get accustomed to it.

“We set out to ride laps around the hotel and it was like the missing piece just settled into place,” she said. “There were some minor goofs: I could no longer put a foot down to catch myself while braking at the same time. But, in the end, it was as intuitive as riding a bike. Project Hero’s adaptive bike program began when Ride 2 Recovery mechanic Scott Moro and Wordin decided they were going to create a way for Delvin McMillian to ride his bike. “Everything we create today in adaptive bike construction is a result of the lessons we learned with Delvin’s bike,” said Wordin. “And I have never seen another organization that builds custom adaptive bikes to our standards and in the way we build them.” As a quad amputee, Delvin had unique challenges but was so dedicated to getting on his bike. We knew we couldn’t let him down,” said Wordin. So Moro and Wordin went to work.

“We needed a solution to a problem that had never been worked out before, especially since at the time many injured Veterans were returning from combat who would benefit from riding a bike. We saw guys who needed and wanted to ride bikes. Delvin needed to shift, brake and steer and at the time there was no way he could do that with his injuries,” said Wordin.

With Moro working as the engineer and Wordin as designer, they pioneered what has become a cycling industry unto itself. “I did a lot of research and couldn’t find anyone who made anything close to what we wanted and those who had tried it had not done it right or up to our standards,” said Wordin. To build the bike, Wordin contacted Stetina at Project Hero sponsor Shimano and asked for one set of every shifting and braking system for every bike on the market, and Stetina delivered.

“It was a lot of stuff! We laid it all out on a table in the warehouse and just got to work experimenting and trying different combinations of things. By February we had it,” Wordin said. “It was not all that complicated, but it sure took a lot of work.”

Today Project Hero is an acknowledged leader in building adaptive bikes and donating them to injured Veterans and First Responders and Project Hero continues to innovate on behalf of injured riders. “We recently adapted a Thompson seat post as a steering device by mounting it vertically on the handlebars that allows riders with prosthetic hands to steer,” said Wordin.

The impact of the adaptive technologies has been substantial and in some ways unexpectedly positive: until she used the butt brake, Ashely hadn’t realized how she had limited herself while riding due to her fear of being unable to brake. With the butt brake, she was able to descend hills without fear, which improved her bike handling skills. “I could actually go as fast as I had always wanted to,” she said. “It was a new form of freedom.” Since getting the butt brake, Ashley has completed more than 30 challenges with Ride 2 Recovery. She is planning to do more but has learned her condition is a progressive central nervous system disorder of a type unknown as yet that is starting to affect her feet and temperature regulation. “It’s disheartening at times,” she said. “But I have faith that, no matter what future limitations I may have, Project Hero has my back.” And in terms of braking, her backside as well.